Behaviour

Background

With the exception of brightly coloured toxic species, most polyclads remain hidden by day under ledges or rubble6. By day this leptoplanid species occurs amongst coral rubble in the intertidal zone. It is found on the underside of rocks, and when an animal’s rock is overturned it will rapidly move from the exposed surface back onto the underside. It is unclear whether this response is an example of phototaxis (a response to exposure to light) or geotaxis (a response to a change in gravity). Negative phototaxis is frequently observed in animals, including a number of planktonic marine species such as larval crustaceans2. Geotaxis is not as common however it has been recorded, for example in larval sea urchins4. However the response in turbellarians has received relatively little study, and an experiment was designed to test which of these stimuli cause the animal to react.

Methods

The experiments were conducted with captive flatworms at night. Worms were placed on a submerged rock in a container and allowed to move onto the underside. A preliminary study had shown that under natural daylight conditions the mean time taken for a worm to move from the exposed surface to the sheltered surface was 26.4 seconds, therefore in each experiment animals were given 30 seconds to react. For each experiment the rock is lifted and held out of the water for the duration. The worms were tested under four treatments, these being:

No stimulus – The rock remains in darkness and is not flipped.

Gravitational stimulus – The rock remains in darkness but is flipped.

Photo stimulus – The rock is not flipped, but is exposed to light from beneath.

Gravitational and photo stimuli – The rock is flipped and exposed to light from above.

The order in which the treatments were applied was varied between the worms, and the worms had a 2 minute ‘recovery time’ between experiments.

Three worms were tested under these four conditions, with three repetitions for each treatment. If the worm moved from the face of the rock that it was occupying onto the opposite side within the designated time this was recorded as a ‘change’ in position. If the worm remained on the rock face that it was occupying over the 30 seconds this was recorded as ‘no change’ in position. Results from the experiments with no stimuli were used to calculate expected values for ‘change vs no change’, and these were then used to determine whether the results for the other treatments differed from expected.

Results

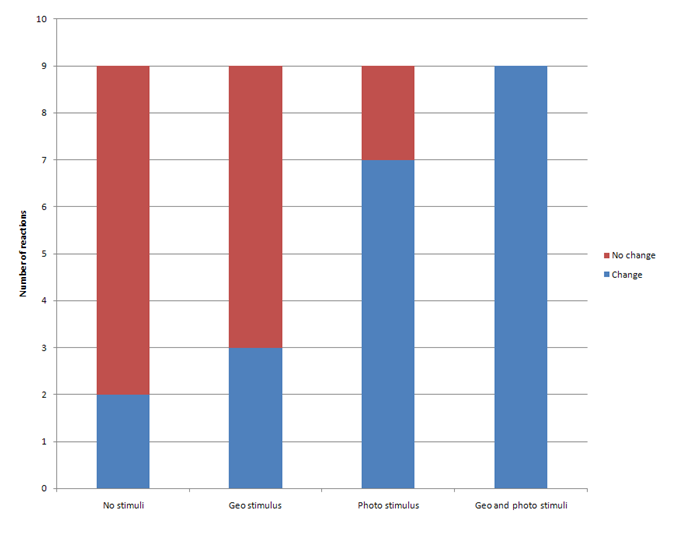

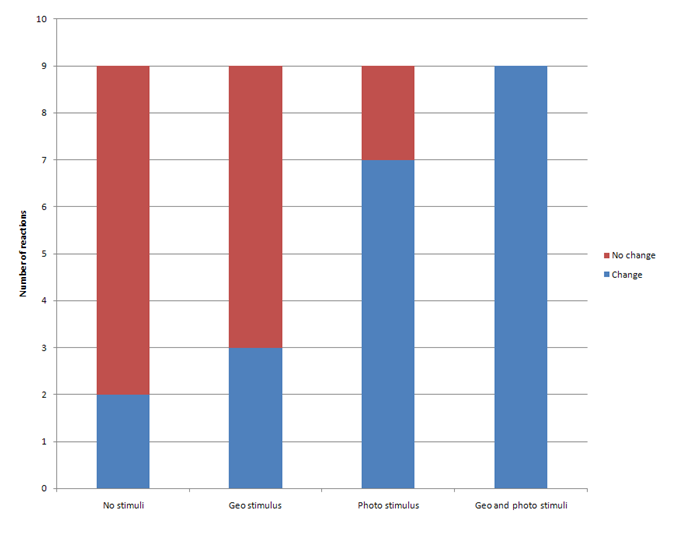

The probability of a worm changing position when no stimuli were applied was 2/9, this was used as the expected value for further analysis. The response to a gravitational stimulus did not differ significantly from the expected value (Chi-squared: Χ2 = 0.643, df = 1, p = 0.423, fig. 1). However the response to a photo stimulus did differ significantly from the expected value, with more worms changing sides more frequently than would be expected (Chi-squared: Χ2 = 16.07, df = 1, p = 0.00006, fig. 1). Additionally the response to a combination of gravitational and photo stimuli differed significantly from the expected value, with more worms changing sides than would be expected (Chi-squared: Χ2 = 31.5, df = 1, p = <0.00005, fig. 1). Although worms changed position more frequently when a combination of gravitational and photo stimuli were applied (fig. 1) this did not differ significantly from expected values (taken from the results of the photo stimulus experiments) for the response to a photo stimulus alone (Chi-squared: Χ2 = 0.286, df = 1, p = 0.593).

Figure 1: A graph comparing the response of flatworms under four different conditions

|

Discussion

The results clearly show that the reaction shown by the flatworms is an example of negative phototaxis. The gravitational stimulus does not appear to affect the worm’s behaviour. Desiccation is likely to be a problem for animals living in the intertidal zone of reefs due to high daytime temperatures and long periods of emersion. Therefore, it is suggested that the negative phototaxis response shown by the flatworms is a reaction to reduce the risk of desiccation. The greatest risk of desiccation would be when exposed to sunlight during the day. In contrast, the risk of this would be reduced in the cooler temperatures of night, or on the shaded underside of rocks by day. The finding that the flatworms show little reaction when a rock is flipped in the dark could therefore support the suggestion that the observed response is a defence against desiccation. Observations suggest that the response to light is reduced when the worms are submerged, although unfortunately it was not possible to test this. However this may be worthy of further investigation, and would again suggest that the response to light when out of water is a defence against desiccation. |