Reproduction

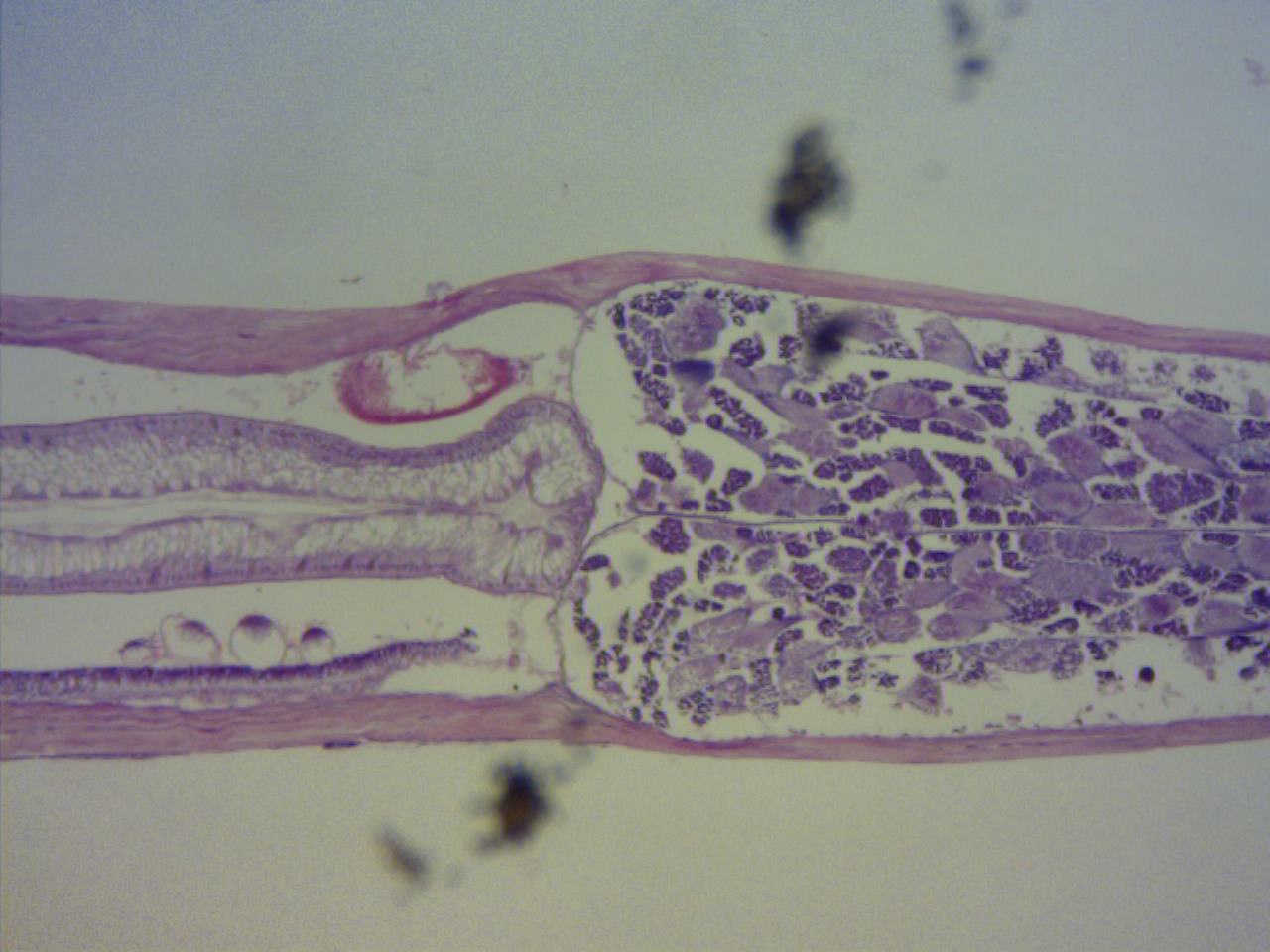

All chaetognaths are hermaphrodites, meaning they possess both

male and female sex organs; however, these are separated spatially by septa (fig 1), and

temporally as they mature at different times in their life-cycle (Ruppert et al. 2004,

Foster 2006, VIMS).

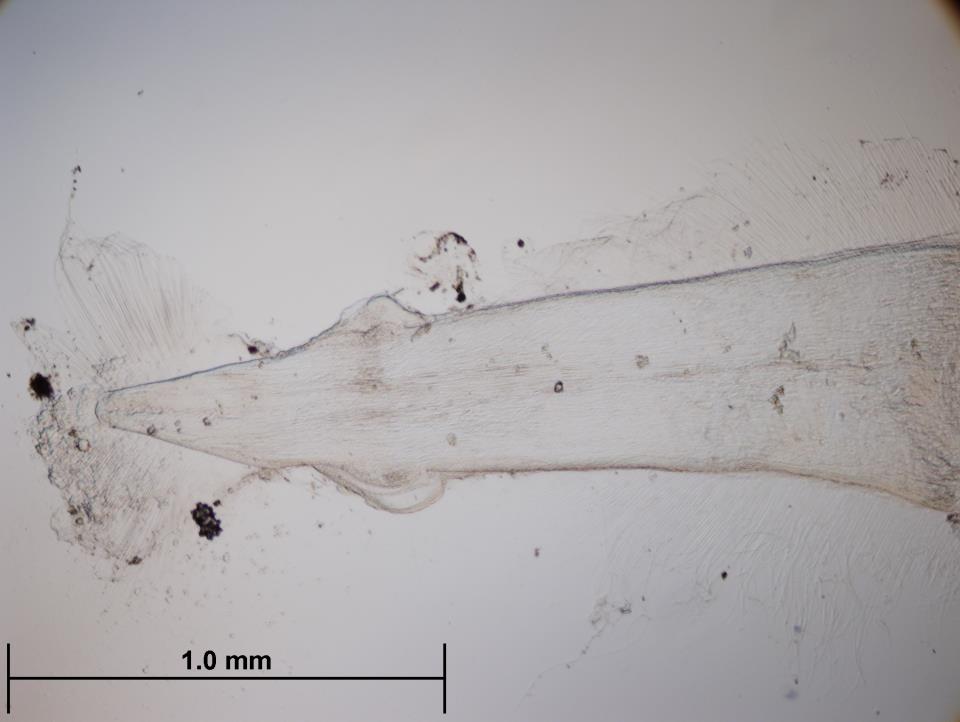

The male’s sperm are located in the tail of the organism,

and are released via seminal vesicles (fig 2) located near the caudal fin. Courtship

behaviour is thought to be initiated by visual signalling in some species (Ruppert

et al. 2004). Whilst the transfer of

a spermatophore occurs when two individuals interlock with their grasping

spines, and rub against each other causing the seminal vesicles to be ruptured and

the spermatophore to be deposited on the body of the other individual (Ruppert et al. 2004, Foster 2006).

The sperm

then make their way to the gonopores and oviducts, which are located in the posterior

of an individual’s trunk, where the eggs are internally fertilised (fig 3). Following fertilisation,

the eggs are released into the water column via a gonopore, where they directly

develop into miniature chaetognaths in as little as one day (usually 1-3 days).

Chaetognaths are believed to have a life cycle that lasts about 1-3 months.

One exception to this method of external development has

been identified. Some species of Eukronhia

spp. do not release their fertilised eggs into the water column, instead

they brood them in a marsupium-like pouch formed by the lateral fins, where

they then hatch from (Ruppert et al. 2004).

Regeneration:

Not much is known about the regenerative ability of

chaetognaths. However, Duvert et al.

(2000) was able to show Spadella

cephaloptera had wound healing capabilities, as they were able to survive

for up to 30 days following the amputation of either their head or tail. This study

proved that even with the loss of its head, S.

cephaloptera was able to attack prey, mate, and lay fertilised eggs,

however as they could not eat, they were unable to produce immature eggs.

Figure 1: Dissection microscope view of a stained section of a chaetognath showing the trunk-tail division.

Figure 2: Dissection microscope view of the tail section of a chaetognath showing the caudal fin and seminal vesicles.

Figure 3: Dissection microscope view of a stained section of a chaetognath showing the oocytes |