Materials and Methods

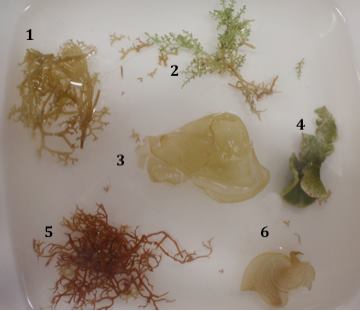

A 1.4m raceway was setup with 4 equally spaced divisions at one end (each with an internal gap of 9.5cm). Six algae species (1, 2, 5 Laurencia spp., 4 Halameda spp., 3 Ulva spp. and 6 Padina gymnospora) were chosen to represent the available algae in A. dactylomelas local foraging area. Of these 6 algal species, 4 samples were randomly chosen by assigning each species a number and using a random number generator to pick 4 samples for each trial. 10 adult A. dactylomela individuals (ranging in length from about 25 to 35cm) were utilized throughout the trial, so that individual was given a turn in each trial time group.

Raceways were filled with enough water (approximately 25cm deep) to cover the animals and were completely flushed out between each trial to ensure that there was no contamination of the next trials. Trials were setup by randomly selecting 4 algae samples and leaving them in the raceway with no active water circulation for 10 minutes prior to placing in an A. dactylomela individual. In each trial, the individual was placed half way between the entrance of the divisions and the end wall of the raceway (so as limit distance bias). The individuals were then each observed for 10 minute and their behaviour recorded according to the following key:

O – No movement

N – Moved away from the algae options

R – Waved rhinophores towards samples of algae

M– Seemed to chose an algae and move towards it within 10 minutes

MC- Changed directions after initial choice

E – The individual seemed to select an algae species and began to eat.

Each response was either marked with a 1 for yes or 0 for no. The 10 A. dactylomela individuals were starved for 24 hours prior to the trial to encourage a fast and positive response to the algae. The trials were run in time 3 groups: morning (8:30am to 11:30am), afternoon (1pm – 4:30pm) and evening (7:30pm to 10:30pm). Both the animals and algae samples were collected from the reef flats on south-east side of Heron Island (23°26′31.20″S 151°54′50.40″E), within the shallow intertidal to sublittoral zone.

Results

In all trials, animals first responded by waving their rhinophores before choosing to move in any particular direction (as seen clearly in the video at 0.12 seconds).

The above video has been designed to be shown in double time and depicts just one of the most common responses that was observed during the feeding trials. Once an individual had been placed into the raceway and "sensed around" with its rhinophores, it would pick one direction, most likely towards a particular sample of algae and begin feeding. The final picture is of the radula which are used to draw the algae into the mouth, and are usually only exposed during feeding.

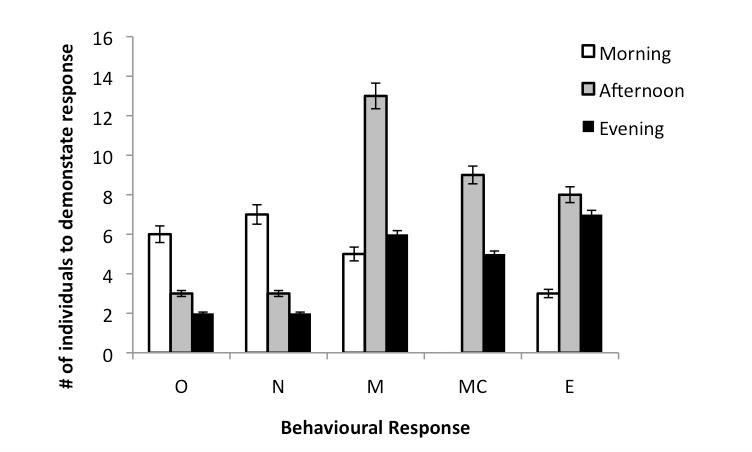

Figure 1: Shows the averaged behavioural responses for each of the grouped individuals, for each time-slot (morning, afternoon or evening). The letters O, N, M, MC and E each respond to the following behavioural key; no movement, moved away from the algal samples, moved towards the algal samples within 10 minutes, moved towards one sample before seeming to change direction and beginning to eat respectively.

The highest exploratory and feeding activity was observed between the afternoon (1:30pm to 4:30pm) and evening period (7:30pm to 10:30pm). Feeding and activity seemed to slow down around sunset but resumed once again after dark, although with less enthusiasm than was seen in the afternoon. One average, the period of highest inactivity or indifferent behaviour towards offerings of food was seen during the morning (8:30am to 11:30am).

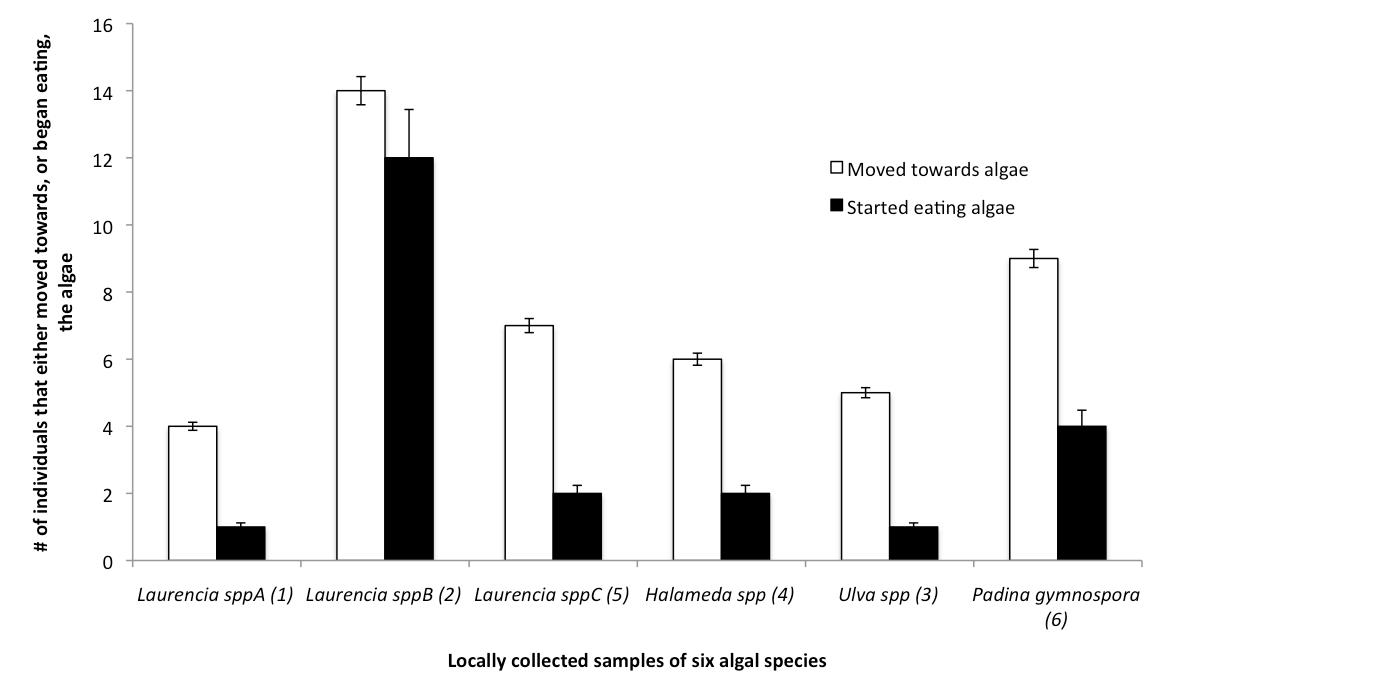

Figure 2: Shows which of the six sampled species of algae A. dactylomela moved towards and started eating most frequently.

In figure 2 it can be seen that there was apparent preference for Laurencia spp. B and a secondary preference for Padina gymnospora. There was no significant observed difference between A. dactylomela's choice of algae in the morning, afternoon or evening sessions.

Discussion

From these feeding trials it can be inferred that, at least out of this algal selection, A. dactylomela show a marked preference for Laurencia spp B. As a red algal species, Laurencia could definitely provide the necessary faunal chemicals for the Aplysia to use to construct of its chemical defense.

Another general trend observed from these results was that of elevated feeding and exploratory behaviour in the evening. The extensive use of rhinophores for what seems to be a full sensory inspection of the immediate environment suggests that A. dactylomela do indeed rely more on their sensory abilities than their sight. This allows them to move freely around at night and still be able to forage successfully for food under the cover of darkness. This both confirms previous observational reports that state that A. dactylomela are a nocturnal species, and asks the question of why they are nocturnal when they have been personally observed to successfully forage during the day.

A second theory arises of why these animals may find it beneficial to forage at night. As simultaneous hermaphrodites, A. dactylomela will often congregate in groups (commonly of 2-8 individuals) to form large “mating chains”. The response to chemical cues and consequent location of large algal turfs may therefore be little more than a biological beaker for a communal gathering site.

|