Cyclicity

Stichopus hermanni are sea cucumbers which are often seen on sandy areas within the reef zone. They are benthic feeders and are slow moving. Therefore it is difficult to determine when they are most active. A study was conducted during a week’s trip to Heron Island research station on the Great Barrier Reef, Australia, to determine what time of day they are most active. This was done by periodically collecting faeces. The theory was that the more faeces collected over a set period of time, the more active that cucumber had been previously. The time it takes for food to travel through the digestive system of S. hermanni was determined in order to calculate the time it had been active.

Four individuals of species Stichopus hermanni were collected off the reef at Heron Island and were placed in a tank at the research station. Sand also taken from the reef was placed in the tank as a source of nutrition. Each individual cucumber was weighed (combined total weight of 4129g). Every hour for a period of 24 hours, faeces from within the tank was collected, dried and weighed. After the study was completed, the cucumbers were released back onto the reef. Meanwhile, one individual S. hermanni was placed in a separate tank at the research station, however, without any sand or alternative source of food. This was to determine how long it takes for food to travel through the digestive tract. Faeces were collected periodically until no more found in the tank. At this point, the cucumber is frozen and dissected to be sure all sand and food particles are clear from the intestines.

As a side experiment, it was attempted to sew the dissected cucumber back up to see if it would survive, however, due to the mutable catch tissue, sewing proved to be very difficult. The cucumber eviscerated its insides, detaching from the base of the mouth. The cucumber was placed back together and held together using latex gloves. The gloves were removed the next day, and the cucumber was released, still alive and on the mend.

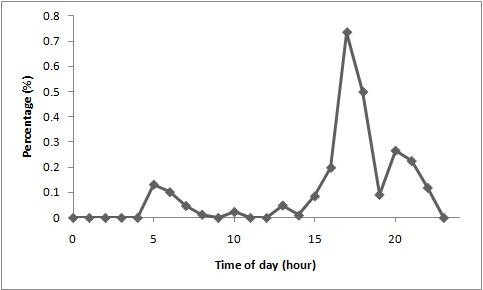

It was determined that it took a maximum of 6 hours for food to travel through the digestive tract of Stichopus hermanni. It was found that there is a peak of faeces collected in the evening (figure 1). This would indicate that there is a peak level of feeding activity around midday. This study produced significant results with peak activity occurring in the middle of the day. However, as they were removed from their natural environment, the stress may have altered the feeding patterns which would affect these results. More studies need to be conducted in the future over longer periods of time.

Figure 1. Percentage of total weight of four S. hermanni of faeces collected over 24 hours. There is a peak of faeces collected in the evening, indicating a peak in activity in the middle of the day.

|